The struggle against violence that we confront in the post 9/11 world cannot be effectively and expediently won if we do not shatter the clout of toxic masculinity

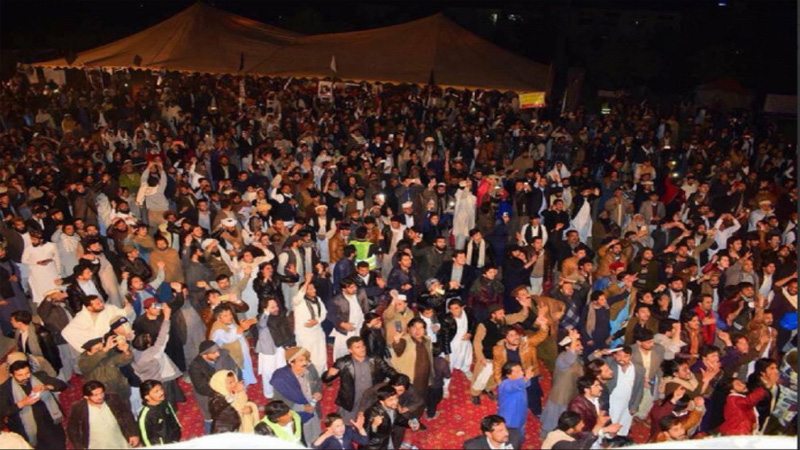

Very few people have written on the Pashtun long march. The marchers had not only gathered in Islamabad against post-9/11 politics and the security regime in the country but also to reject patriarchal values of Pashtun society. The march was unprecedented because it rejected Pashtun masculinity which has become the cultural economy of war in the region.

Very few people have written on the Pashtun long march. The marchers had not only gathered in Islamabad against post-9/11 politics and the security regime in the country but also to reject patriarchal values of Pashtun society. The march was unprecedented because it rejected Pashtun masculinity which has become the cultural economy of war in the region.

In the ten-day long sit-in, the Pashtuns, who are otherwise known as ‘primitive’ and conservative, repeatedly shouted, ‘Nar Pashtun, Batur Pashtun,’ (who is) the manly and brave Pashtun? Thousands of protestors chanted arduously and unequivocally, ‘Manzoor Pashtun, Manzoor Pashtun’ — the young star and leader of the sit-in.

In Islamabad, the redefining of the (manly) Pashtun culminated in Manzoor: the intrepid man who stood for the oppressed with strong conviction, and who dared to speak spenay khabarey, truth to power. Moreover, while addressing the sit-in leader of the Pakhtunkhwa Milli Awami Party, Mahmood Khan reinforced that an honourable Pashtun is one who stands for his rights and democracy.

Such was the zeal that the participants of the march intercepted any speaker who reiterated the long-held myth of ‘ghayourqabail’ (fearless tribesmen). The marchers emphatically rejected such notions of manhood which manipulate them into laying down their lives recklessly for the state’s sake. ‘No more deaths,’ the crowd would roar, and ask mockingly, ‘What ghairat (honour) is it to live under colonially sanctioned FCR?’ In fact, tears in the eyes of Manzoor Pashtun and other men while recounting torture stories at the hand of the Pakistani military and the suffering of hundreds of women defy such narrative about Pashtun men.

Unfortunately, the rhetoric of ‘brave tribesmen’ is tenaciously held and widely promoted by the Pakistani state itself. The state invokes it from time to time so as to exploit the hyper-masculinity of the tribesmen in proxy wars as cheap labour or non-military combatants. Unsurprisingly, the primary victims of such conflicts are the tribesmen themselves. Indeed, it would be disingenuous if we try to comprehend the half-century-long terror politics in the Pashtun region between Afghanistan and Pakistan without unravelling the relationship between the Pashtun masculinity and war.

In Pashtun society, the male individual has to undergo a torturous rite of passage in which he has to take control of his heart and mind to qualify as a ‘real’ man — fearless, aggressive and indifferent. Although such harsh standards have helped the people to some degree in coping with war trauma, ironically this highly internalised manliness is itself perpetuating violence. This is evident in how militants make use of manly values. The establishment of a ‘total male society’ by the Taliban, scholars have argued, was a powerful expression of Pashtun manhood entangled with the desire to control sex derive so as to foster ascetic propensities and strong male camaraderie among the militants.

White male ethnographers had no access to women or female-spaces therefore their ethnographies of Pashtun culture not only represents the unchanging orientalist imagery of the tribesmen, but are also incognizant of women’s perspectives. Ironically, such understanding of Pashtun society is now conjured up largely by none other than Pashtun ethno-nationalists who claim to be building their politics on the legacy of anti-colonial leaders

To a very large extent the contemporary idea of Pashtun manhood and the understanding of the Pashtun way of life, Pashtunwali — courage (tora), revenge (badal), hospitality (melmestia), and protection of women (namus) etc — were authored by colonial authorities. White male ethnographers had no access to women or female-spaces, therefore, their ethnographies of Pashtun culture not only represent the unchanging orientalist imagery of the tribesmen but are also incognizant of women’s perspective on the subject. Ironically, such understanding of Pashtun society is now conjured up largely by none other than Pashtun ethno-nationalists who claim to be building their politics on the legacy of anti-colonial leaders.

The struggle against violence that we confront particularly in the post 9/11 world cannot be effectively and expediently won if we do not shatter the clout of toxic masculinity. The Pashtun Long March ceded space to many women activists — make no mistake, they were not just token women; the protestors listened to them, got enthralled by their revolutionary speeches, and exalted their fearlessness in the face of the oppressive state. Letting women speak of their grievances and giving them the chance to lead the masses, particularly when the suffering of women was a central issue in the march, will help the men to oppose war and its concomitant security regime, and the masculinity which feeds into it.

Saif Ullah Nasar: The writer teaches anthropology and is a member of Awami Workers Party. He can be reached at nasarsaifullah@gmail.com

Pashtun Times Latest News

Pashtun Times Latest News